And, as in so many other areas of American life, those averages obscure a deeper divide: The US is the only developed country to have high proportions of both top and bottom performers. America spends the most-about $1.3 trillion a year-yet the US ranks 25th out of the 34 OECD countries in mathematics, 17th in science and 14th in reading. How immense? According to a report from the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, global spending on education is $3.9 trillion, or 5.6 percent of planetary GDP. And that creates immense opportunities for both for-profit entrepreneurs and nonprofit agitators like Khan. After decades of yammering about “reform”, with more and more money spent on declining results, technology is finally poised to disrupt how people learn. It’s a fair question, with an increasingly sure answer: The next half-century of education innovation is being shaped right now. That is high impact, but what happens in 50 years?” “I could have started a for-profit, venture-backed business that has a good spirit, and I think there are many of them-Google, for instance,” says Khan, his eyes dancing below his self described unibrow. 'Kids should be problem solving with each other should be peer-tutoring' There is no employee equity there will be no IPO funding comes from philanthropists, not venture capitalists. It’s a prototypical Silicon Valley ethos, with one exception: The Khan Academy, which features 3,400 short instructional videos along with interactive quizzes and tools for teachers to chart student progress, is a nonprofit, boasting a mission of “a free world-class education for anyone anywhere”. The company’s 37 employees, mostly software developers with stints at places like Google and Facebook, are the types who know when to laugh.

It involves LeBron James (a Khan Academy fan), three-point shots and sophisticated algorithms called Monte Carlo simulations.

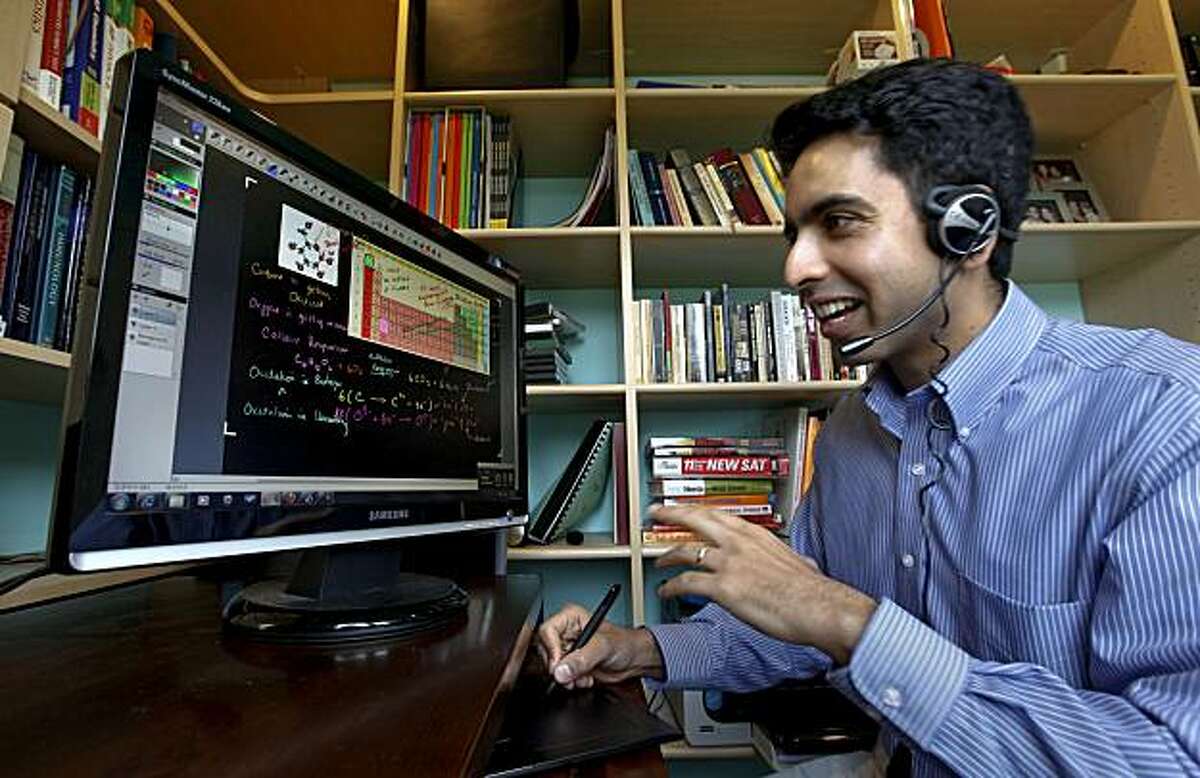

Pivoting, Salman Khan, the 36-year-old founder, cracks a sports joke appropriate for someone who holds multiple degrees from MIT and Harvard.

At the weekly organisation-wide meeting, discussion about translating their offerings into dozens of languages is sandwiched between a video of staffers doing weird dances with their hands and plans for upcoming camping and ski trips. Despite the cramped, dowdy circumstances, youthful optimism at the Khan Academy abounds. The headquarters of what has rapidly become the largest school in the world, at 10 million students strong, is stuffed into a few large communal rooms in a decaying 1960s office building hard by the commuter rail tracks in Mountain View, California. Salman Khan of Khan Academy has reached more students than any teacher in history

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)